Burnie kids tell their stories

Join us for these memories of growing up “a Burnie kid” from the early days soon after the founding of the Burnside Homes for Children, through to the return from the mountains just after the second World War. This is a piece of Australian history that is both intensely personal and a part of our shared nation-hood...

Some of the material in this within is very emotional, and may trigger intense or painful memories for adults who were in residential care as children.

If this is the case for you, we encourage you to seek emotional support as you process these memories.

One option for support is to visit the Find and Connect website

“Burnside Homes is considered the greatest achievement of Sir James Burns’ life.”

Burnside historyBurnside history

The Burnside Presbyterian Orphan Homes were established in North Parramatta in 1910 with an initial grant from Sir James Burns of 45 acres and £1000. The inspiration for Burnside Homes came when he was travelling by train from the Blue Mountains to Sydney and noticed the orphanages and institutions of the Catholic Church. He felt his own Presbyterian Church should provide similar facilities. The Presbyterian Assembly received his idea very positively, as they had expressed similar concerns in their 1906 report on destitute children. As a result they began to plan the construction of the orphanage.

The Burnside Homes were modelled on the Quarrier Homes in Scotland which used the ‘cottage system’. Under this system each matron ordered her own provisions through the homes store. She also did her own cooking so that the children could live, sleep and eat in their own home and play on their own lawn.

Each Burnside Home had approximately 30 children, which was a huge improvement on the state homes, such as Randwick Asylum for Destitute Children, which had over 800 children at the peak of its operation. These overcrowded institutions could be desperately unhappy and unsafe places for children.

The establishment of the Burnside Homes is considered the greatest achievement of Sir James Burns’ life. Others followed in this humanistic work, including notable Burnside figures Dr Ronald Macintyre and Mr Monty Burns. The Burnside Homes for Children had ceased operating as a residential orphanage by 1986, but continues its important work with children and families as a part of UnitingCare, through provision of a wide range of family support programs across NSW. The guiding principle is to provide the social support required to maintain children within well-functioning families.

UnitingCare Burnside was recently voted in the top 10 of Australia’s Philanthropic Gifts.

Thanks to Sir James Burns’ generosity and vision, UnitingCare Burnside has grown and evolved over the past century to continue to meet the needs of families, children and young people.

“Arriving at Burnside could be daunting...”

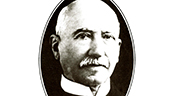

Buildings and groundsBuildings and grounds

Huge grounds, stately buildings, impressive architecture… arriving at Burnside could be daunting, although to some children it felt as though they were coming to live in a castle…

And Burnside was an impressive place in many ways; with its own farm, dairy, laundry, hospital and school…. Burnside was almost self-sufficient. This was a great advantage in providing healthy food for the children, especially during the Depression.

One of the most significant aspects of life for the children was which house they lived in. This determined their friends, their Matrons, how strict the rules they lived under were and even how much food they received.

“Struggling parents or other relatives were faced with a terrible choice...”

Family circumstancesFamily circumstances

Some of the Burnie kids were true orphans in that both of their parents had died, but many came from families that had suffered other misfortunes including:

- The serious illness or death of one parent

- The breakup of the parents’ relationship

- Tuberculosis

- Alcohol dependency

- Desertion

- Financial stress

- Work requirements that did not leave sufficient time for the care of children

- Family conflict or disagreement

In a time without much government support or help, without affordable childcare… struggling parents or other relatives were faced with a terrible choice…

In addition, for many ex-Burnsiders, there are unanswered questions regarding their childhoods… Many only have bits and pieces of information, or have heard several different versions of events from family, friends or official sources…

“...and sometimes they didn’t know that Burnside was to be their new home.”

Arrival at BurnsideArrival at Burnside

Arrival at Burnside was a very big moment for a child – often they weren’t aware where they were headed or what was happening, and sometimes they didn’t know that Burnside was to be their new home… Parents sometimes left without saying goodbye…

“...a home to 23 Irish-Protestant orphans whose home was burnt over their heads.”

Irish and Scottish boysIrish and Scottish boys

17 Scottish children from the Quarrier Homes, at Bridge of the Weir near Glasgow, arrived on board the Jervis Bay on 18 May, 1939 and most settled into Reid Home. The 17 arrivals included 4 girls and 13 boys. They were greeted with a special event including playing by the Pipe Band.

The Burnside Annual Report of 1939 includes a photo of the children and the caption 'Invasion from Scotland'.

The Reid home made it possible for our Chairman, Sir James Burns, and Mr Andrew Reid (the donor of the home) after consultation with other members of the Board, to offer, in response to an advertisement in the London "Times," a home to 23 Irish-Protestant orphans - whose home, at Ballyconree, Galway, was burnt over their heads.

Those boys duly arrived in Australia and were accommodated in the Reid home. Several of them have been placed in suitable positions, and we trust will do credit to themselves and the Homes that have helped them.

Superintendent's Report, 1922

“I still can't eat porridge to this day.”

Daily routineDaily routine

What were the daily routines of life for Burnie kids?

Some kids liked the food, some didn't care for most of it… Some had enough to eat, some were always hungry… their experiences of the food depended on a number of things.

- A typical day (4:56)

- Fairly obsessed with food (6:54)

- For about a month of the year, we used to be the best-fed kids in Burnside... (1:25)

- I can give you a typcial meal... (3:45)

- Memories of food - I hated Tuesdays (5:28)

- Morning routines - Even at 6 years old (2:11)

- My biggest problem with the meals... (1:08)

- No time for homework (0:41)

- Sunday was a lost day, Saturday was a better day (8:55)

- We originated muesli! (0:36)

- We used to be VERY regimented and we HAD to be (0:20)

- Why the Burnie kids were lucky during the War (1:14)

“Most children at the school were Homes children, although there were a few ‘outsiders’.”

School daysSchool days

Burnside had its own school, Burnside Public School, which was built in 1922 by Sir James Murdoch at a cost of 17,000 pounds. For many years it was known as the Murdoch School. The school was built mainly due to the difficulties of transporting the Burnside Homes children to North Parramatta School. Most children at the school were Homes children, although there were a few ‘outsiders’.

“We used to clean the saucepans with ash from the fire.”

Chores and workChores and work

In an era when most Australian children did more work than the Aussie kids of today, what was expected of the Burnie kids in the way of chores?

How did they go about getting them done?What effect did all of this have on the kids?How much work and responsibility did the older kids have?- A terrible responsibility for a 14-year old kid (1:22)

- Deliveries by billy cart (1:25)

- The only thing I disliked about Burnside... (0:54)

- We used to pretend we were fairies, angels (0:59)

- We were doing men’s work… and never got a word of thanks (1:01)

- We were paid 2 shillings and 6 pence every week (1:24)

“...a big part of how Burnside was known in the community.”

Music and danceMusic and dance

Burnside provided a number of opportunities for the kids to be involved in music. True to its Scottish heritage, Burnside was particularly well-known for its Pipe Band and Highland Dancers, both of which achieved great success, and even produced some medal-winners. The Band and the Dancers provided an ongoing connection to the Scottish traditions of the Presbyterian Church which founded Burnside, and were also a big part of how Burnside was known in the community. Boys were selected to be part of the Pipe Band, and regularly rehearsed with the Band Master. Although girls were not involved in the Pipe Band, the Highland Dancers and Pipe Band did rehearse together. At some points, Burnside also had a choir, and additionally Burnside school groups once or twice performed on the Parramatta Town Hall stage.

“Playing barefoot - we were winners!”

Sports and gamesSports and games

Lots of practice, committed teamwork and a bit of 'attitude' meant Burnside was very well-known for sport! This was especially true for boys, who played rugby and cricket, with lots of opportunities to play competitively against other schools. Burnside’s teams were very successful.

Girls had some opportunity to play sport, particularly a game known as Vigoro, which was based on cricket, and played between Burnside Homes. Vigoro was not played against other schools, and it received much less attention than cricket or rugby.

One of the special features of Burnside was the swimming pool and the lessons that were given to every child.

- Burnside boy written up on front page of London Times as next Don Bradman... (2:47)

- Everybody learnt to swim (2:28)

- Girls' sports... vigoro, sewing, dancing! (1:10)

- Great fun trying to look over the wall (0:58)

- Rugby League - We challenged the local grammar school... they never spoke to us again... (1:22)

- Rugby Union – only the boys at the front had boots! (1:52)

- Undefeated for 20 odd years (0:23)

“As a Burnside child you never ever played indoors, ever...”

Free timeFree time

"Play is the work of the child" - Maria Montessori …and play helps to prepare children for their grown-up lives…

So how did Burnie kids play?

“...the older boys used to sneak out and raid the orchard.”

MischiefMischief

Did the kids get up to any mischief?

“I carried my brother all the way to the hospital after he jumped out Reid Home window.”

Hospital visitsHospital visits

The original Margaret Harris Hospital was opened in 1917 especially for caring for the children of Burnside Homes.

“...the children never forgot the occasional special event”

Events and excursionsEvents and excursions

During some of this period, daily life was very regimented, and therefore the children never forgot the occasional special events that enlivened an otherwise routine existence. There were a few trips out, and a few special occasions at the Homes.

Visiting Day was the toughest for many kids – most didn’t have any visitors, so the day could be a sad one. For those lucky kids who did have someone who visited, it was a time when connections with family were kept alive.

“World War II... Burnside children and staff were sent to the mountains”

War timeWar time

During World War II, the Australian government assumed the use of the Burnside buildings and grounds. Most of the Burnside children and staff were sent to the mountains, to what was portrayed as a safer environment…

This move had an impact on everything, including family ties, education and play…

Back at Burnside, the army took over the majority of the Burnside buildings and used them for their Eastern Command Base. Many of the older boys remained in the Farm Home at Burnside to live and work. Every day, morning and night, food and milk were sent up on the train to the mountains. Teachers also travelled to the mountains daily to teach the children.

“Burnside... had its own rules, own slang, even a special language...”

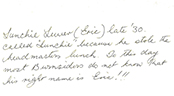

A separate little worldA separate little world

In many ways Burnside was a country of its own; as well as being virtually self-sufficient food wise, it also had its own rules, own slang, even a special language… In addition to their separation from the wider world, the Burnie kids were separated from the kids in the other Burnside houses…

“Who were you at Burnside?”

Names and identityNames and identity

What were you called?

Did you have a nickname?

Were you ever referred to as a ‘number’?

How did you feel seen by the wider society?

“Living apart made it hard to keep up close family bonds”

Sisters and brothersSisters and brothers

Circumstances at Burnside often kept the children away from their sisters or brothers... Living apart made it hard to keep up close family bonds… Other kids in the Home could become even closer than sisters or brothers...

“Treasured moments of kindness have stayed with ex-Burnsiders for many years...”

FriendshipsFriendships

What did mates mean to Burnie kids?... What was the social world like within Burnside?

Material goods speak volumes about daily life in other times and other places… The first half of the 20th century was a world without iPods, and there was no TV at Burnside yet, but what ‘stuff’ was a part of daily life there?... Did the Burnie kids have any stuff of their own?

Treasured moments of kindness have stayed with ex-Burnsiders for many years…

There were also sadder moments when they were treated harshly…

- A matron steals Doreen's scenty soap, and two elderly ladies give a never-forgotten gift (3:14)

- At least we had each other (0:28)

- That's all we possessed... (1:43)

- The only cuddle I ever had... (0:50)

- There was actually a lady... And we didn't even know... (0:59)

- Toothpaste in those days (0:31)

- We had that sense of belonging to each other (4:14)

- Where ever she was, I was too (0:22)

“I went on to become a Science Teacher and taught for 40 years.”

Life after BurnsideLife after Burnside

Transitions are an important part of life for everyone, and also a vulnerable time. Burnie kids had a range of experiences of the transition from Burnside to the outside world. Some had help and support from their family or extended family, while others did not have this available to them. Some were still caught up in family conflict. Some felt well supported by Burnside, and others felt lost or abandoned.

- I was privileged to be in the Farm Home... (1:49)

- It was all gone, I was lost... (1:03)

- It was like a stranger picked me up... (0:45)

- They didn't prepare you... (2:30)

- They had to have a live-in job, and so did we (3:46)

- They were very good to you if you left... they took you back to Burnside (3:36)

“That era was a difficult time in history and Burnside did the best they could.”

Impacts and returningImpacts and returning

What were some of the impacts of being ‘a Burnie kid’ on the adults they became? The good and the bad…?

No one chooses the circumstances of their birth or their childhood but we’re often judged on our background or origins.

Some ex-Burnsiders have experienced negative judgments about growing up at Burnside.

How have the grown-up Burnie kids dealt with this tricky social issue?

Going back to the places and people of our childhood is momentous… How have the grown-up Burnie kids felt about revisiting such significant chapters in their own life stories?

- A bit more sympathetic (1:14)

- Doesn't affect our LIVES, but the way we THINK (4:59)

- Fancy being frightened of that... (1:10)

- For 40 years I never came near the place... (2:15)

- I like to think of the happy times... (2:10)

- I'm very grateful (0:45)

- If I could get out of it, I wouldn't tell... (3:39)

- It was a good upbringing (3:02)

- More conscious of the needs of children (2:31)

- On the now closed-in verandah... (1:16)

- Really this is your day... (1:12)

- Some people didn't like to admit their connection with Burnside (0:42)

- The general atmosphere of camaraderie (2:09)

- The world outside was so big (0:26)

- We couldn't show love (3:38)

- You people have done a bloody good job (1:02)

“Dedicated with great affection to all the Burnie kids, and those who cared for them.”

Thank you and feedbackThank you and feedback

Many thanks to all who shared their memories, and to you for joining in the experience of these stories.

Dedicated with great affection to all the Burnie kids, and those who cared for them.

Memories kindly shared by Vera Baikie (formerly Harris), Doreen Wehrstedt (formerly Bayliss), Betty Burge-Lopes (formerly Malley), Leslie Butt, John Cullum, Ron Dyer, Albert Farrell (‘Ikey’), Irene Gourlie (formerly Seabrook), Moreen Hull (formerly Belcher), Stanley James, Jim Last, Beryl Martin (formerly Wild), Jack Swinton, Malcolm Williamson and Fred Wingrave.

Interviews conducted in 1995 and 1996 by: Fiona Cameron, Lyn Milton and Barbara Horton (Burnside Archivist)

This initiative has been made possible as a result of the ‘Your Community Heritage’ 2012/13 grant funding and the in-kind support of UnitingCare Children Young People and Families Management and staff.

We welcome your feedback — cypf@unitingcarenswact.org.au